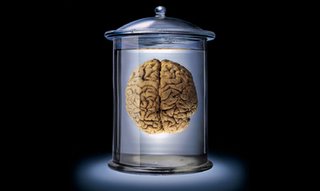

Am I A Brain in A Vat?

I posed this scenario to my class today, eloquently portrayed by philosopher Jonathan Dancy:

I posed this scenario to my class today, eloquently portrayed by philosopher Jonathan Dancy:"You do not know that you are not a brain, suspended in a vat full of

liquid in a laboratory, and wired to a computer which is feeding you your

current experiences under the control of some ingenious technician scientist

(benevolent or malevolent according to taste). For if you were such a brain,

then, provided that the scientist is successful, nothing in your experience

could possibly reveal that you were; for your experience is ex hypothesi

identical with that of something which is not a brain in a vat. Since you have

only your own experience to appeal to, and that experience is the same in either

situation, nothing can reveal to you which situation is the actual one."

(Introduction to Contemporary Epistemology, 10)

I asked them how they would respond to such a claim. "Hoe do you know you're not a brain in a vat right now?" They were a little mystified.

One solution to this is Richard Swinburne's principle of credulity. It is simply this -- your beliefs about the world around you are innocent until proven guilty. If the world seems real, it probably is. The skeptic is the one who has something to prove.

6 Comments:

Chris, I had a couple of questions about the use of Swinburne's principle to respond to sceptical worries.

How does that help someone who wants to know whether to believe he is not a BIV? I'm not sure we have much by way of a solution to the sceptical puzzle if there isn't anything that can be said to the person trying to determine whether a sceptical hypothesis is false. The Principle tells them nothing, it only says if you already believe that you're not, go ahead until proven guilty.

Aside from the utility of the principle, I wonder a bit about its content and justification. How are we to understand the 'until proven guilty'? If it says you may believe p unless you acquire reasons to believe ~p, it seems the principle cannot explain what is wrong with someone who both knows they believe p and that their total evidence relevant to p makes p no more likely than chance (such evidence is evidence that one's evidence fails to make probable rather than evidence that one's belief is probably false). Typically we think one is neither permitted nor reasonable to believe p knowing that their evidence fails to make p highly likely, so would accepting Swinburne's solution require us to deny that the justification of our beliefs can be defeated by undermining?

Those are excellent observations. Let me see if I can respond. Swinburne's principle (for more, check here)I think, is not intended to answer the skeptic's question. It simply shifts the burden of proof. It isn't meant to rebut skepticism per se, rather I think it is meant to rebut radical skepticism. It just isn't going to completely satisfy.

If I consider a case where a belief that p is not more likely than chance, such as my belief that it will rain tomorrow, given that I haven't looked at forecasts, I don't think Swinburne's principle applies. I don't think I could say that "it seems to me that it will rain." I will venture to say that Swinburne's principle applies generally to beliefs that appear to have sufficient evidential backing. To take this discussion further, I'll have to go back and read up.

Chris,

Thanks, that helps some. I have to confess that there is something to the idea that once in place, belief should give way only in the face of evidence against but having said that, it also seems odd to think that adopting a belief should change the demands placed on us as believers. Much more fun then to ask questions of others than offer up answers.

One of the more interesting things I've read about scepticism recently is Williamson's discussion in The Ox. Handbook of Contemporary Philosophy in which he explains that the belief that one isn't a BIV actually serves to make probable that one is by at least a slight degree which suggests that the belief that one isn't a BIV is (at least slightly) falsity-indicative. For me, this was something completely new.

i have only been studying philosophy for a short period but to me this Brain in a vat looks like a pseudo problem. If the world which you think you live is exactly the same as the world created within the vat then surely they are the same thing.

i cant recall who said it but if you have a five pound note, and a perfect replica of the five pound note in everyway, and there is no test to differ one from another, then you have to accept the replica, is in fact a real note. If it possess all of the same qualities and properties, according to Liebniz Law, it must be the same thing.

The problem with accepting the possibility of BIV means that you're also accepting that we can't know anything, even if BIV is possible, because BIV was hypothesized with perception. This puzzle claims that you can't know that you're not a BIV because you're merely using your perception in order to determine it.

However, you've also used your perception to determine the possibility of brain in a vat. Thus by default BIV possibility is false, because as such, in order for it to remain true, the possibility must remain definitive, not questionable. Otherwise your then saying "brain in a vat is possible, is possible." Not only is this a paradox because it need be definitive in order to be a true possibility, but ad infinitum because there's an infinite amount of possibles to justify one another.

No form of Solipsism holds up because all of them imply that you cannot justify any of your believes, or know anything for that matter, but give special pleading to Solipsism. All forms of Solipsism are self refuting.

It's like a watered down version of Nihilism. "There are no truths", well then Nihilism isn't truth.

But that's what epistemology is for. What is knowledge? What does it mean to know something? Stuff like Solipsism, BIV and Nihilism are the extreme that attempt to throw epistemology out the window. However, in doing so, they throw themselves out as well.

If I'm a BIV, then another entity has gone to an awful lot of trouble to create my reality for me.... Why?

Or maybe we are all individual components of a "metabrain" and the universe is the vat.

Post a Comment

<< Home