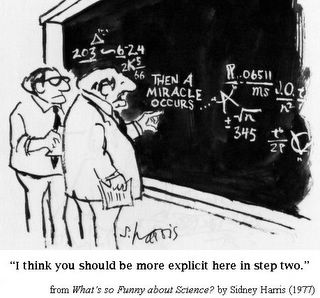

A theologian and an astronomer struck up a conversation at a party one evening. The astronomer declared, “I don’t know why you theologians fuss over things like transubstantiation, substitutionary atonement and predestination. All I need to know about theology I learned in kindergarten – ‘Jesus loves me, this I know, for the Bible tells me so’.” To which the theologian replied, “I don’t know why you astronomers make such a big deal about astrobiology, dark matter and

molecular gas-clouds. All I need to know about astronomy, I too, learned in kindergarten – ‘Twinkle, twinkle, little star, how I wonder what you are.”

We would never accept such a childish understanding of astronomy among adults, but it’s often a different story when it comes to Christianity. Most believers today would see intellectual pursuits and complex, theological discussions as detrimental to the life of faith – something to be avoided. The virtues of “simple faith” are applauded, and we are encouraged to guard ourselves against the enemies of “philosophy and empty deception.”

Anti-intellectualism has had many detrimental effects on the American church, one of which is the spawning of an irrelevant gospel. Most gospel presentations are aimed at felt-needs and emotions, rather than the mind or will. The trouble with this is it fails to reach people who have no felt-need for the gospel. We need to contend for the

veracity of our faith, not merely its psychological benefits. Consider this exchange that recently took place between

William Lane Craig and a frustrated, skeptical student:

“Many students have difficulty grasping the idea that religious belief is anything more than subjective feelings. One student asked, “Shouldn’t we just rely on ourselves instead of placing our faith in some illusion?” When I responded that I had given extensive

evidence that the resurrection was not an illusion, he retorted, “But I have no need to believe in that!” I replied, “I’m not telling you to believe in it because you need to; I’m telling you to believe in it because it’s

true,” which brought loud applause and laughter.”

Another consequence is the marginalization of the church in American culture. When Christians began to withdraw from academia in the 19th century and early 20th century, we left our posts unguarded. As a result, the enemy has invaded and taken over. Now we are unwelcome in the halls of higher learning, and religion is expected to remain a privatized activity.

R.C. Sproul says it well:

“The church is safe from vicious persecution at the hands of the secularist, as educated people have finished with stake-burning circuses and torture racks. No martyr’s blood is shed in the secular west. So long as the church knows her place and remains quietly at peace on her modern reservation. Let the babes pray and sing and read their Bibles, continuing steadfastly in their intellectual retardation; the church’s extinction will not come by sword . . . but by the quiet death of irrelevance. But let the church step off the reservation, let her penetrate once more the culture of the day and the . . . face of secularism will change from a benign smile to a savage snarl.”

The current Creation-Evolution debate (see previous posts) that rages on here in Oz is a prime example. Christians abandoned the universities long ago, and now the chickens have come home to roost. Scientists and educators don’t want us bringing “religion” into the state-sponsored classroom, and Christians don’t want the state contradicting what their children learn in church. When worlds collide – watch out. But it doesn’t have to be this way.

What the church needs is a renaissance of its rich intellectual history. Instead of churches eyeing academia with suspicion, they should be encouraging their young people to integrate their Christianity with their studies and pursue terminal degrees in all fields. We need not only the average believer to love God with her mind, but the academically-gifted must answer the call to defend the Church against her enemies. As

C. S. Lewis puts it, “Good philosophy must exist, if for no other reason, because bad philosophy needs to be answered. . . .The learned life then is, for some, a duty.”

If the Church wants to have an impact in our culture, it must rediscover the life of the mind and its crucial role in the renovation of the soul.